Address

2255 East Evans Ave.

Denver, Colorado 80208

Get in touch

wlr@law.du.edu

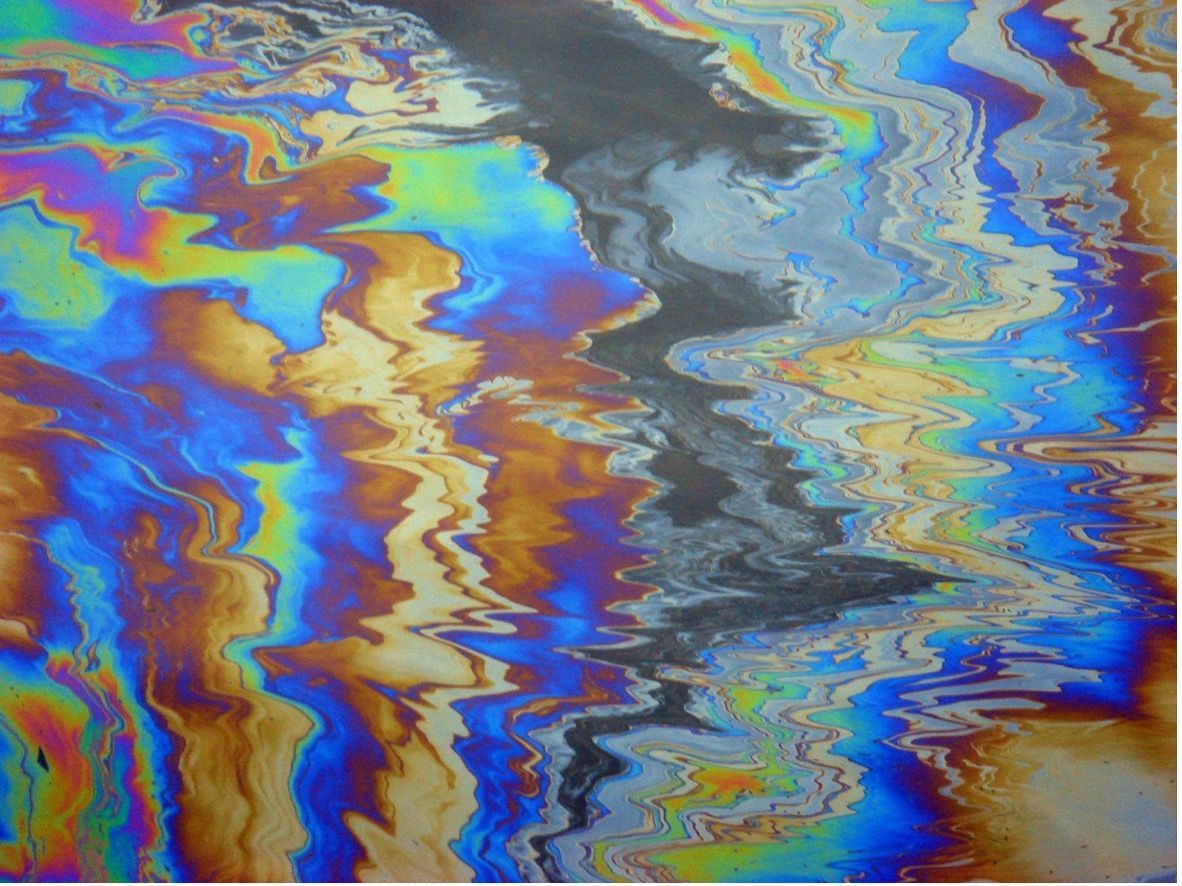

Born of the arid west, the University of Denver Water Law Review fosters discussion and promotes rigorous scholarship on water law and policy.

ABOUT US

The University of Denver Water Law Review is an internationally circulated, semi-annual publication that serves as a high-quality forum for the exchange of ideas, information, and legal policy analysis concerning water law.

MISSION STATEMENT

Born of the arid west, the University of Denver Water Law Review fosters discussion and promotes rigorous scholarship on water law and policy.

2024 Symposium

The 2024 Symposium,

Water as a Nexus: Agriculture and Efficiency in the West, will be held on Friday, April 19th.

Registration is now open. Free for students!

– Seeking Submissions –

The University of Denver Water Law Review is seeking submissions for publication in its upcoming volumes. The Review is an internationally circulated, semi-annual publication that serves as a high-quality forum for the exchange of ideas, information, and legal and policy analyses concerning water law. We welcome submissions from practitioners, professors, judges, students, and all other water law professionals and scholars. The Review prints articles focused on water rights and water rights systems, water conservation and sustainability matters, water planning and development, water equity, and other water-related matters. Manuscripts (as well as any questions) may be submitted by email to wlr@law.du.edu. Publication offers are made on a rolling basis. Thanks for your interest in the Water Law Review. We look forward to reading your submissions!

Recent Blog Posts

Recent Post

University of Denver Water Law Review at the Sturm College of Law

MENU

GET IN TOUCH

Water Law Review

Sturm College of Law

2255 East Evans Ave.

Denver, Colorado 80208

wlr@law.du.edu

All Rights Reserved | Fix8