Address

2255 East Evans Ave.

Denver, Colorado 80208

Get in touch

wlr@law.du.edu

Fish closures have impacts that are beneficial, at least that is the hope.

Over the 2018 summer, Colorado’s Parks and Wildlife Commission (“CPW” or “the Commission”) asked anglers to shelve their waders and rods following voluntary fishing closures on various river sections statewide. Because of low water flows, high temperatures, and dry conditions statewide, CPW asked anglers to help protect the state’s overtaxed fish. These voluntary closures are commendable. But should people circumvent them, it could be devastating for both the fish and anglers alike. If anglers decide to shirk these voluntary closures, what kinds of legal mechanisms exist to enforce them? And, what potential legal ramifications exist for violators and Colorado?

Fortunately, CPW has a tackle box full of statutory and regulatory authority for enforcing these actions. To better understand the legal mechanisms at play and the possible ramifications that exist, this post delves into the statutory mechanisms that CPW may utilize to effectuate fishing closures. It also explores CPW’s delegated regulatory authority to invoke fishing closures across the state. Lastly, it discusses potential legal ramifications for both violators and Colorado.

Statutory Mechanisms Affecting Fishing Closures in Colorado

In addition to asking for voluntary closures, CPW has a comprehensive legal apparatus in place to enforce fishing closures under Title 33 of the Colorado Revised Statutes. Title 33 sets the administrative responsibilities for Colorado’s wildlife, including licensing requirements for hunters, fishers, and recreators. It also sets rules and regulations governing the state’s wildlife programs. Moreover, Title 33 grants CPW with broad statutory authorityso that Colorado’s wildlife is “protected, preserved, and managed for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the people of [Colorado] and its visitors.”

For example, Section 33-1-106(1)(a), C.R.S., grants CPW the power, if necessary, to shorten or close seasons on any species of wildlife in specific localities or statewide. Additionally, Section 33-6-120, C.R.S. provides corresponding criminal penalties for fishing out of season or in a closed area. It permits the levying of fines, assessing license suspension points, and makes it a misdemeanor offense for any violation.

Another statutory provision with related authority is Section 33-1-107, C.R.S. This section allows CPW to adopt rules and regulations for the management of agency-controlled lands, property interests, water resources, and water rights. To wit: CPW may restrict, limit, or even prohibit the time, manner, activities, or numbers of people that use these areas. Moreover, CPW may regulate in a manner that maintains, enhances, or manages property, vegetation, wildlife, and any object of scientific value or interest in any such area.

CPW also has angling specific authority to regulate fishing licenses. Under Section 33-1-106(1)(e), C.R.S., CPW regulates when persons may apply for a permit, the length of time the permit is valid, where the permittee may fish, and more. This statutory provision also provides CPW with the power to draft rules or regulations to help meet its statutory obligations thereto. Additionally, CPW possesses similar criminal enforcement authority (under Sections 33-6-105, 33-6-106, and 33-6-107, C.R.S.) to suspend the privilege of applying for, purchasing, or using a license; levying of fines; or to bring criminal charges against violators.

Another legal mechanism outside of Title 33 for enforcing fishing closures is the citizen petition provision under Section 24-4-103(7), C.R.S., of the State Administrative Procedure Act.This provision permits any interested person to petition CPW for the creation, modification, or removal of a regulation. And provides citizens with a nexus to participate in the rulemaking process; serving as a powerful device for individuals and groups alike to enforce these closures.

Last but not least, the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”) creates an interesting interplay between federal and state law. The ESA provides an extensive framework of laws that help protect and conserve species listed as threatened or endangered. This includes the Section 9 “take” prohibition, which makes it unlawful for any “person” to “take” any listed endangered or threatened species as designated through regulation. The statutory terms, “person” and “take,” are broad. For example, the term “person” literally applies to everyone—from state and local government officials, private citizens, federal government officials, and more. In addition, the ESA imposes both civil penalties (up to $25,000) and criminal sanctions (a maximum $50,000 or imprisonment of up to one year, or both)for taking a listed species. With these sorts of extensive prohibitions and penalties in place, both federal, state, and local officials could utilize Section 9 to implement fishing closures on waters where listed fish species inhabit.

Additionally, Section 7of the ESA requires federal agencies consult with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to “insure that any action authorized, funded, or carried out by [them] is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered species or threatened species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of [critical] habitat.” Although Section 7 applies only to federal agencies and federal agency actions, its reach is far wider. Because federal agencies are involved in the construction, development, permitting, licensing, or financing projects in Colorado, Section 7 could affect state and local agencies or private entities that require any sort of federal permit, authorization, or funds. Thus, making Section 7 an applicable statutory tool that could affect state entities requiring federal authorizations, permits, or funds to operate.

To date, Colorado is home to seventeen animal species listed under the ESA—five of which are fish species. Therefore, the federal government (via the Fish and Wildlife Service) also has authority to impose fishing closures based on its authority under the ESA and other similar wildlife conservation and preservation statues. Additionally, the federal government—in the spirit of cooperative federalism—can partner with CPW to inform and enforce these fishing closures. Thus, providing CPW with, not only more tools in its tackle box, but a valuable and powerful ally.

Through the comprehensive statutory regime in Title 33 and beyond, CPW has ample gear to help institute fishing closures throughout Colorado. Additionally, CPW may partner with, or rely on federal agencies to implement federal statutes (like the ESA) to help supplement its authority to effectuate these fishing closures around the state. Thus, demonstrating a robust set of statutory legal mechanisms at CPW’s disposal to implement fishing closures if need be.

Regulatory Mechanisms Affecting Fishing Closures in Colorado

The legislature has also delegated CPW the power to issue regulationsthat can help effectuate fishing closures. These regulations are extensive and forge an effective apparatus by which CPW may carry out these closures. CPW can regulate the dates and times of fishing, enact water specific or emergency closures, and other, more water body specific regulations.

First, CPW may regulate the dates and hours when anglers may catch fish. The regulation starts from the position that fishing shall be open day and night, year-round. But an exception allows CPW to otherwise restrict the dates and hours of fishing through other regulations, thereby driving a truck through the regulation. Thus, CPW may limit or close fishing around the state.

A second powerful regulation at CPW’s disposal permits the agency to prohibit fishing when in the process of adopting water specific regulations. Per 2 CCR 406-1:104(E), CPW may prohibit fishing “when necessary to:

- Protect threatened or endangered species[;]

- Protect spawning areas[;]

- Protect waters being used in Commission research projects[;]

- Protect new acquired access to fishing waters[; and]

- To protect the integrity of sport fish, native fish or other aquatic wildlife populations.”

This regulation holds a dual purpose. The regulation gives CPW time to craft and mold regulations to pinpoint the needs of fish and address them accordingly. It also allows CPW to prohibit fishing while it enacts these water specific regulations to benefit Colorado’s fish. Hence serving as a mechanism to effect fishing closures while CPW issues necessary regulations.

Third, CPW also has the power to close fishing waters in times of emergency. Under the regulation, fishing waters may be closed for up to nine months. CPW may authorize an emergency closure after determining that water conditions have reached a level where fishing could cause unacceptable levels of fish mortality. (E.g., fish that become stressed because of low oxygen levels and increased food competition due to minimal flows and high temperatures—conditions that led to the voluntary closures over the 2018 summer.) The regulation enumerates five criteria for initiating an emergency closure:

- Daily maximum water temperatures exceed 74˚ F or the daily average temperature exceeds 72˚ F;

- Measured stream flows are 25% or less of the historical average low flow for the time period in question;

- Fish condition is deteriorating such that fungus and other visible signs of deterioration may be present;

- Daily minimum dissolved oxygen levels are below five (5) parts per million[] [; and]

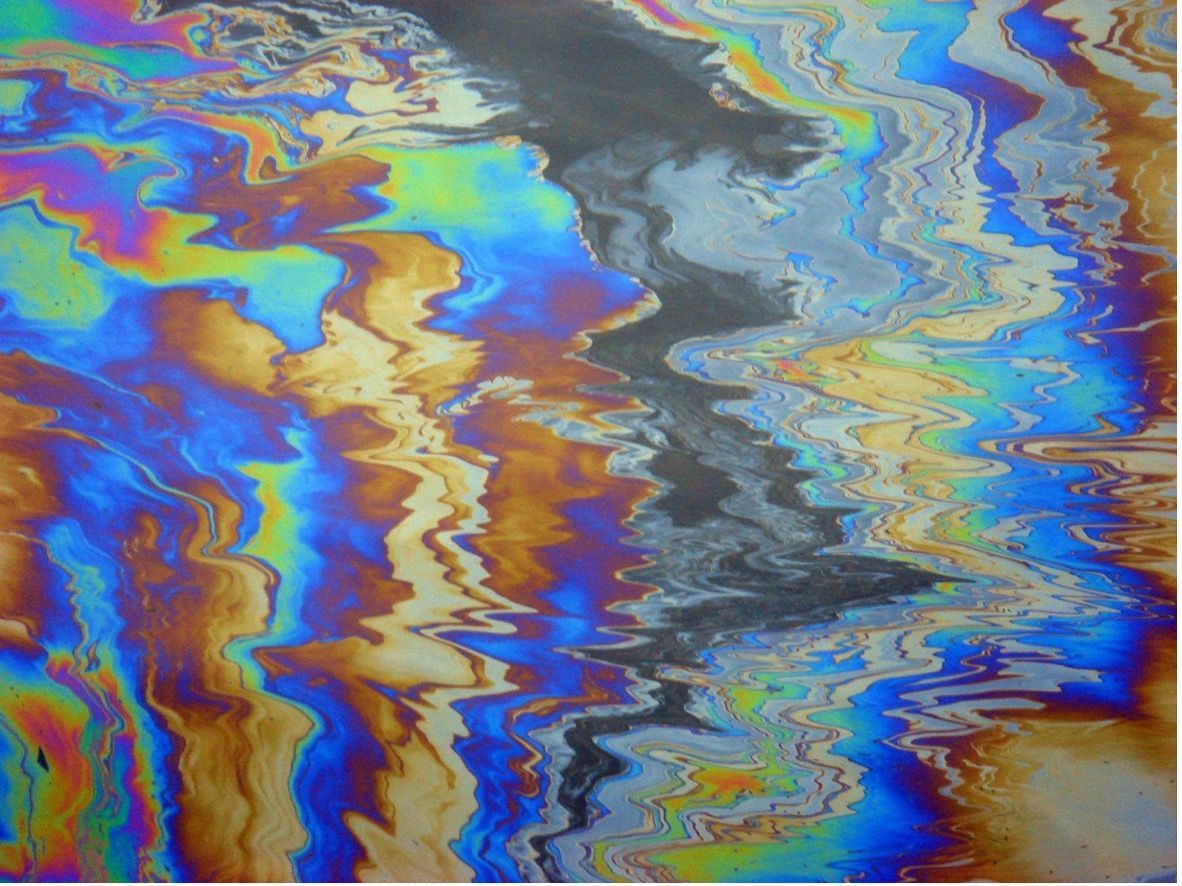

- When a natural or man-caused environmental event such as wildfire, mudslides, oil spills or other similar event has occurred, resulting in the need for recovery time or remedial action for a fish population[.]”

Curiously, there were several riversthat would have been subject to emergency closures. (CPW instead opting for voluntary closures of affected waters.) If these sorts of “emergency” conditions persist, CPW would be justified in closing off sections of river to fishing. Therefore, this regulation serves both as a powerful legal mechanism to enforce fishing closures, and as a reality check if anglers choose not to follow them.

Fourth and finally, CPW has also established specific management guidelines that afford further protection—explicitly for trout—for Colorado’s most pristine fishing waters, known as Wild Trout Waters and Gold Medal Waters.To be designated a Wild Trout or Gold Medal water, a water body must meet certain criteria. Wild Trout Water must be a habitat capable of sustaining a wild trout population, and with the primary fishery management objective of maintaining a wild trout population. Accordingly, Gold Medal Waters must produce a minimum trout standing stock of 60 pounds per acre, a minimum average of 12 quality trout per acre, and be accessible by the general angling public.

Once designated as Wild Trout or Gold Medal waters, CPW must administer the waters according to four specific management guidelines. The first guidelines states that CPW should manage these waters in a way that promotes the preservation and protection of the trout and their aquatic habitat. Although the first guideline does not give CPW affirmative powers or regulatory authority, it serves as an important signpost for how CPW must manage these waters.

In contrast, the second guideline serves as a more viable enforcement tool. It states that CPW may request mitigation from a person or agency that contributes to the loss or degradation of a Wild Trout or Gold Medal water. The regulation does not define or discuss what is meant by mitigation, or required of persons or agencies who are tasked with mitigating a water. But it is fair to surmise that it is not cheap. For example, the mitigation costs alone for the Northern Integrated Supply Project—as exhibited in the Draft Final Fish and Wildlife Mitigation and Enhancement Plan—hovered around $35 million. Thus serving as a powerful tool to not just recoup costs, but as a stick to ward off anglers who may choose not to tolerate CPW’s fishing closures.

Under the third guideline, specific to Wild Trout waters, CPW may recommend special regulations to sustain or enhance wild trout to provide quality-fishing opportunities. This allows CPW to create and import special regulations that protect fish. These regulations could include restrictions, closures, or bans on fishing to sustain or protect wild trout populations. And, therefore, could help bolster CPW’s authority to enforce fishing closures across the state.

The fourth management guideline for Gold Medal waters provides CPW with the authority to manage the fish in these waters. Principally, CPW can recommend regulations for the purposes of maintaining or exceeding the Gold Medal fish population criteria. Again providing CPW with authority to enforce fishing closures in these waters.

CPW’s regulatory authority allows for more acute control of fishing closures in Colorado. In tandem with its statutory counterparts, these regulations act as a bulwark against anglers who choose not to abide by the voluntary closures that were in effect over the summer. And help to ensure that CPW is capable of putting further measures in place should these voluntary closures fail to alleviate the stress on Colorado’s fish species.

Legal Ramifications for Violators & the State

Violators of these legal or regulatory closures and the state could face significant legal trouble. For violators of the law, the ramifications are quite plain: fines; loss of, or the privilege for applying for a license; and even criminal charges. These outcomes are certain. But should violators of either legal or voluntary closures push fish populations to the brink, CPW may be forced to restrict or prohibit fishing all together—a loss for all who love this activity and for those just learning to. And rather than voluntary fishing closures, anglers may soon have their favorite fishing holes locked up, with the key thrown away.

For Colorado, the impact would felt in the pocket book: loss of revenue from anglers from in- and out-of-state, and from tax paying businesses that rely on fishing to turn a profit. Hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation in general are big business in Colorado: contributing approximately $6.1 billion to the state’s economy. In 2017, 1,100,609 people hunted or fished in Colorado—supplying $218.7 million in funding for CPW to manage and improve the state’s outdoors. From an economic standpoint, it would appear, the closures are “bad for business.” (What with people not spending money to fish and all.) However, a short hiatus is better than a permanent loss of resource. This rudimentary economics perspective, however, over-simplifies the problem: should fishing holes run dry the state will not only lose revenue, but a precious wildlife species (something that cannot be replaced by superior business acumen). Thus making voluntary closures good for both Colorado’s fish and economy.

Moreover, should the situation surrounding the State’s fish become dire, the Federal Government could supplant Colorado’s control through further implementation of the ESA or other federal statutes. Should that happen, Colorado’s management over its wildlife would be vastly limited and the people of Colorado’s voice over how to conserve and preserve our resources could be quelled. And in a state with a proud outdoor recreation history and booming recreation-oriented economy, this would be a huge blow to Coloradans.

The startling prospects of sweeping fishing closures, including loss of fish species and loss of revenue and business in Colorado could come to fruition should we choose not to act and save our fish. Tightening our appetite for fishing and exercising discipline is the only way to ensure that this problem does not balloon into something uncontrollable. And while it may be tough, it is vital that we take this step: not just for the avid angler, but for those who fish only occasionally, or people such as myself who enjoy seeing fish at the aquarium or on the occasional rafting trip.

CPW has broad statutory and regulatory authority to help protect Colorado’s fish. It is encouraging that CPW is seeking angler’s help to protect fish through cooperation and volunteerism. Should this cooperation or volunteerism fail, however, CPW is well equipped to protect the State’s fish through a comprehensive set of statutory and regulatory legal mechanisms. While the ramifications for violators and Colorado seem grave, through collaboration between state and federal government entities, as well as anglers, it is possible that voluntary closures may solve the problems facing our state’s fish. Conversely, should these voluntary closures fail, CPW is well suited to protect Colorado’s fish by employing the legal mechanisms at its disposal.

Sources

Coyote Gulch, @COParksWildlife Announces Additional Voluntary Fishing Closures in Northwest Colorado, Coyote Gulch (Jul. 27, 2018), https://coyotegulch.blog/2018/07/27/coparkswildlife-announces-additional-voluntary-fishing-closures-in-northwest-colorado/.

Colo. Parks & Wildlife, 2018 Fact Sheet, https://cpw.state.co.us/Documents/About/Reports/StatewideFactSheet.pdf (last visited Nov. 11, 2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 33-1-101 (2018).

Colo. Rev. State § 33-1-106(1)(a) (2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 33-6-120 (2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 33-1-107 (2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 33-1-106(1)(e) (2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 33-6-105 (2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 33-6-106 (2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 33-6-107 (2018).

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 24-4-103(7) (2018).

Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. § 1538 (1973).

Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. § 1536 (1973).

Colo. Code Regs. § 406-1:101 (2018).

Colo. Code Regs. § 406-1:104(E) (2018).

Colo. Code Regs. § 406-1:104(F) (2018).

University of Denver Water Law Review at the Sturm College of Law

MENU

GET IN TOUCH

Water Law Review

Sturm College of Law

2255 East Evans Ave.

Denver, Colorado 80208

wlr@law.du.edu

All Rights Reserved | Fix8